How can immersive experiences help people imagine and build new worlds?

We designed an immersive experience with Dr Mwenza Blell to explore haunting, reproductive justice and abolitionist practice.

The client

No client this time—this was a collaboration with Dr Mwenza Blell.

The brief

Mwenza wanted to collaborate on a project that brought together our work on building imagination and creating new possibilities and her work on reproductive justice, surveillance and data, and the idea of haunting. We developed a brief for the project together focused on experiences of haunting, reproductive justice, and supporting abolitionist practice.

Finding our shared interests

We met with Mwenza over a period of a few months to work out the boundaries of our shared interests. We settled on haunting, reproductive justice, and abolitionist practice because of the overlaps we saw between these areas. Reproductive justice isn't just about the right to have or not have a child, but the ability of people to raise children in worlds that support their ability to grow up well, safe, and healthy. It has to affirm people's ability to live. In contrast, carceral systems limit or reduce people's ability to live through the restriction of their freedoms. Whilst these life-limiting systems affect much of society, they disproportionately affect Black people. So reproductive justice requires abolition.

Mwenza's work has previously explored the relationship between haunting and reproductive justice. Her work builds on Avery Gordon's idea that haunting is how abusive systems of power make their impacts felt, especially when they are supposedly over and done with, or when their oppressive nature is continuously denied. In this project, then, we wanted to explore people's individual relationships to haunting in relation to reproductive (in)justice, and carceral systems.

What we did

We've developed projects previously that are centred on creating fictional alternative worlds for people to step into, imagine different possibilities, and bringing something back to their lives from these fictional worlds. This is pretty standard speculative design practice—creating something as if it's come from another world, some future or past, and seeing how people interact with it. In this project, though, we wanted to explore what it was like to give people more of a felt sense of these different futures. What does it feel like to live in a future where there is reproductive justice and carceral systems have been abolished? How can people take that feeling forward?

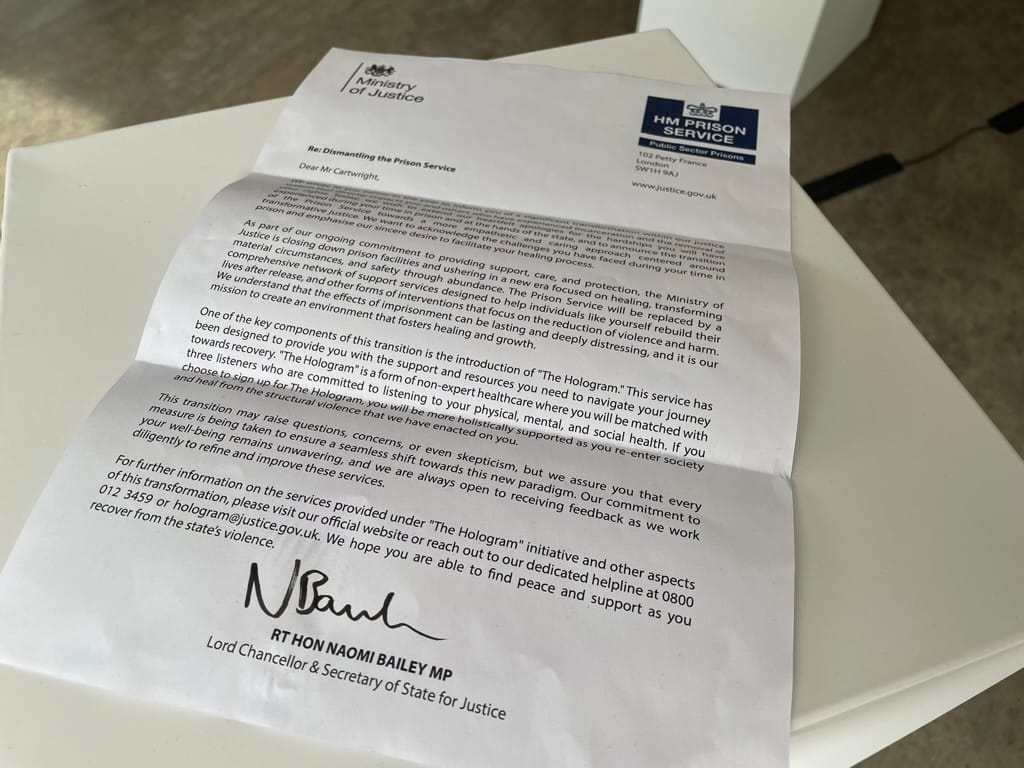

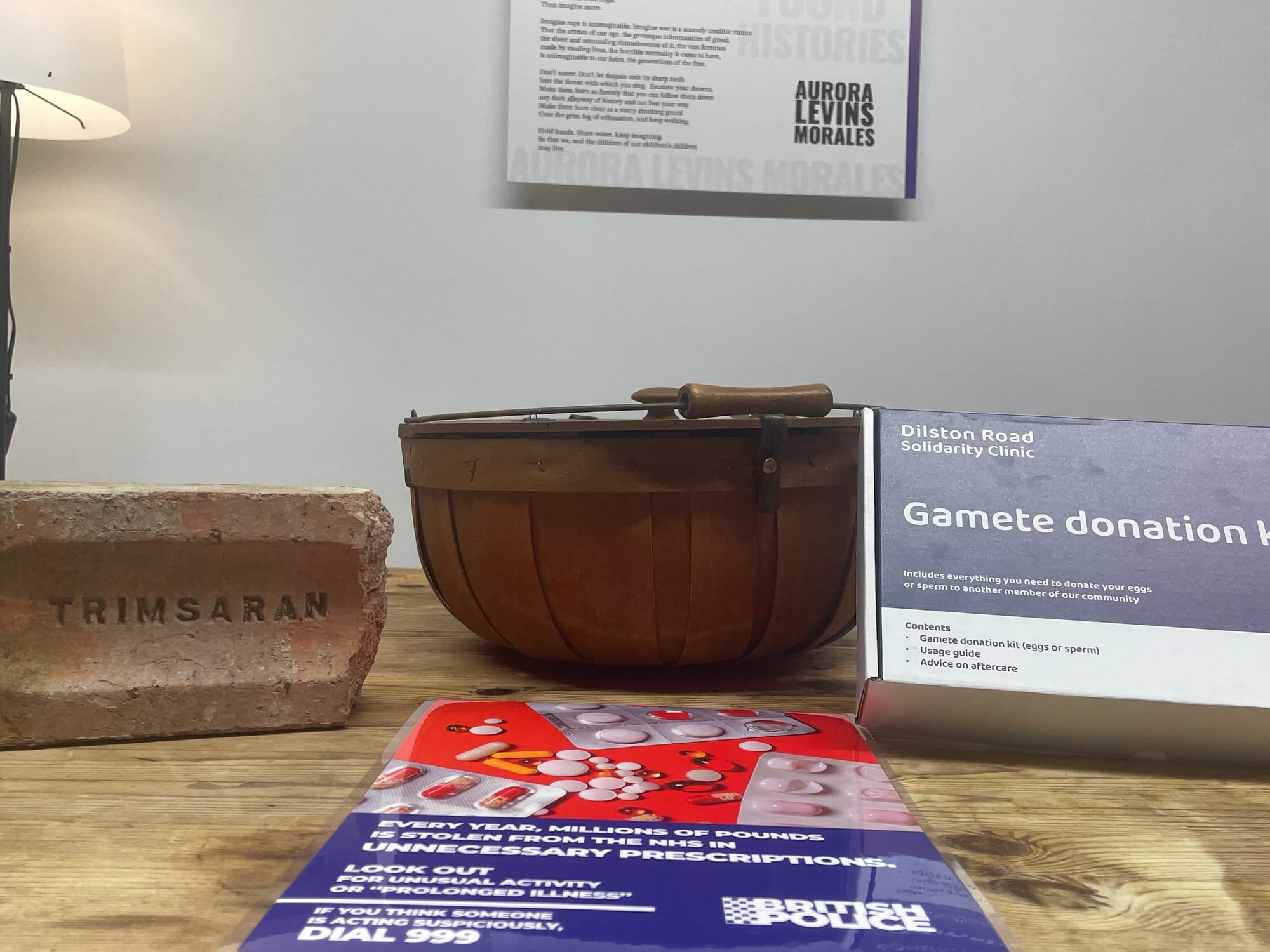

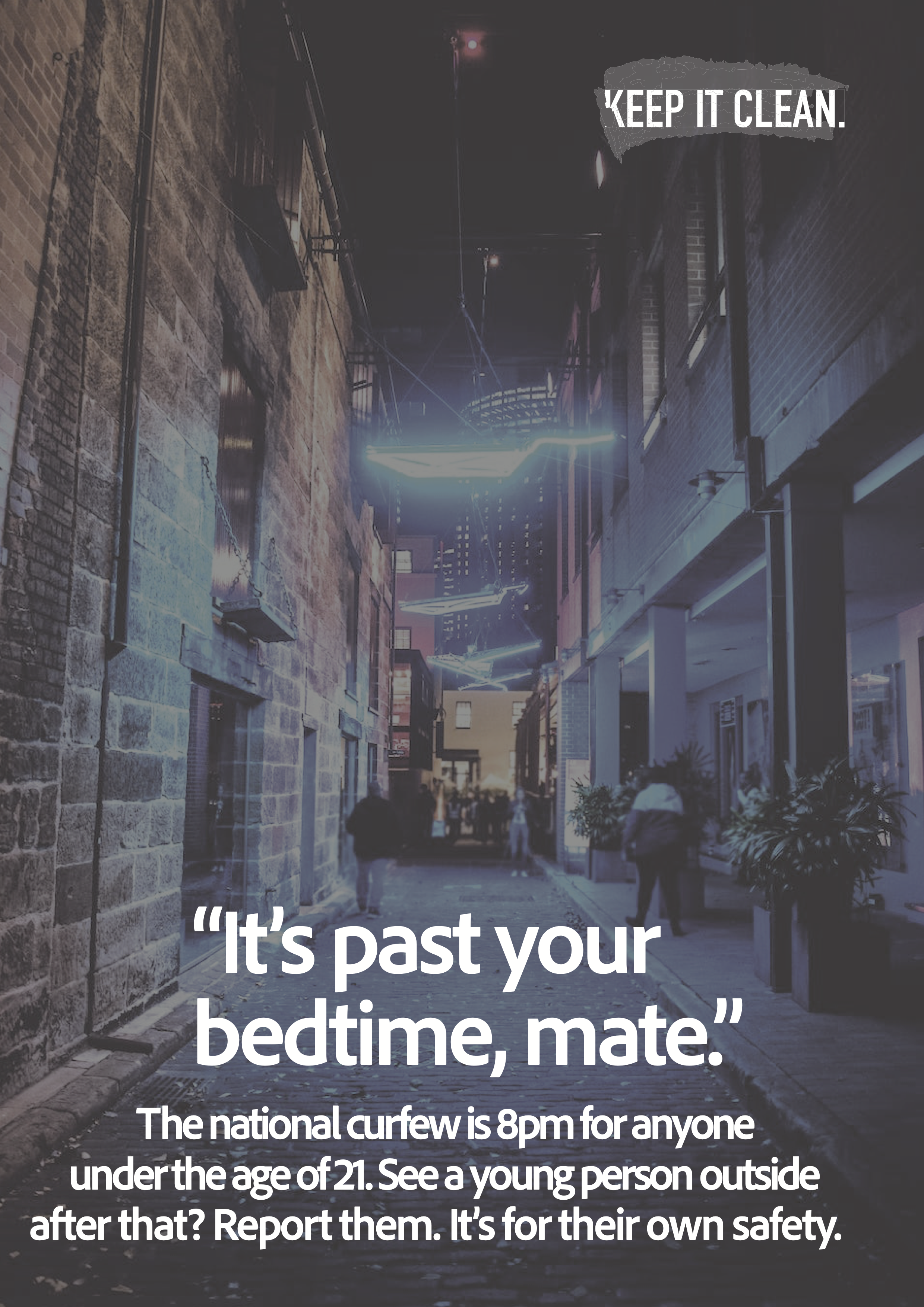

To do this, we decided to make an immersive experience for this project: The Museum of Lost Futures//Archive of Found Histories. The experience that we developed centred on objects that we designed from potential futures, histories, or pasts, stories written by Mwenza based on her research attached to each of these, and an audio soundscape that guided people through the space.

Because we wanted to explore how to help people feel different kinds of feelings, we wanted people to feel safe in the room, so we asked everyone who attended to come with someone that they cared deeply about and felt comfortable with. We wanted to use this relationship as a design material in the room: if people could experience this with someone that they already had a deep relationship with, their ability to imagine different futures and bring something from those futures forward into their lives might be increased.

In the experience itself, two people who are close would enter the space together, be greeted by Mwenza or myself, and then be told in the waiting room. Then, the audio soundscape would begin to play, and a voice would welcome them to the Museum of Lost Futures. It would tell them about the museum and ask them about their relationship, before inviting them into the space.

Audio used with permission from Ciaran Clarke, Mwenza Blell, Leah Lockhart, Leonie Rowland and Dean Pomeroy.

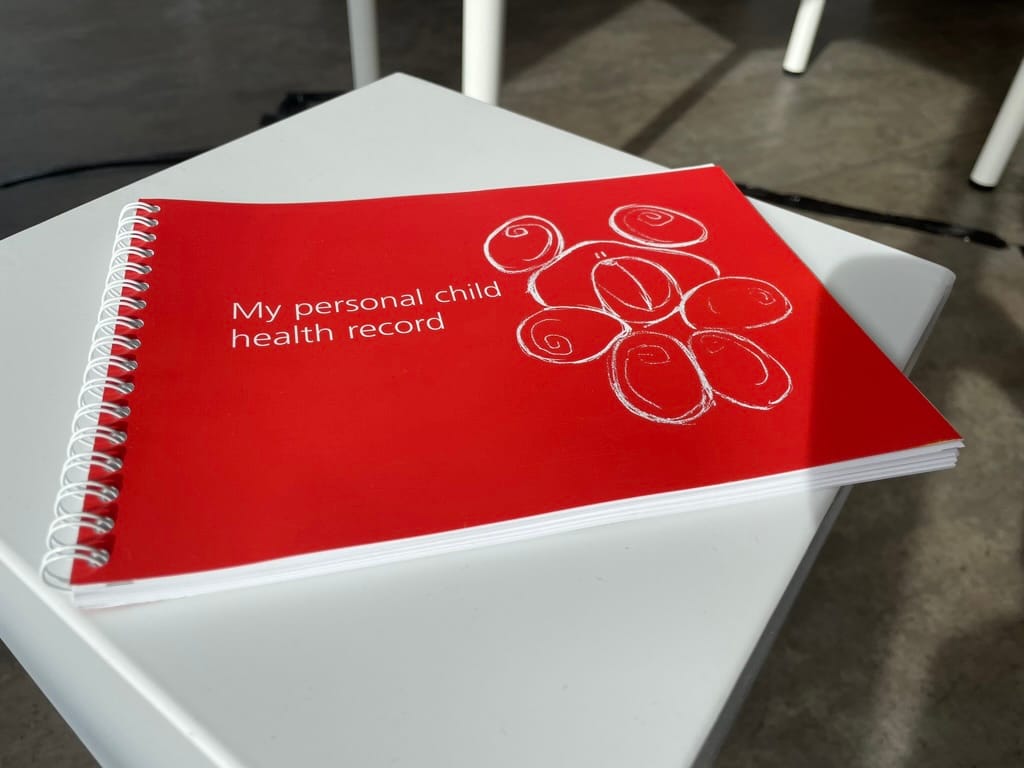

There, they'd enter the museum properly, filled with objects from potential futures, histories, other worlds—or even our world. Some of the objects that produced the strongest reactions in people were things they couldn't quite tell if they were real. The "See it. Say It. Sorted." poster, for example, uses text that is on real posters that live in train stations across the country. Some people were sure this related to some other world than our own. Living in sort-of-fiction in this way helped to expand people's possibilities of what the world could be.

Whenever people touched an object, a story would play from someone involved with the object's history.

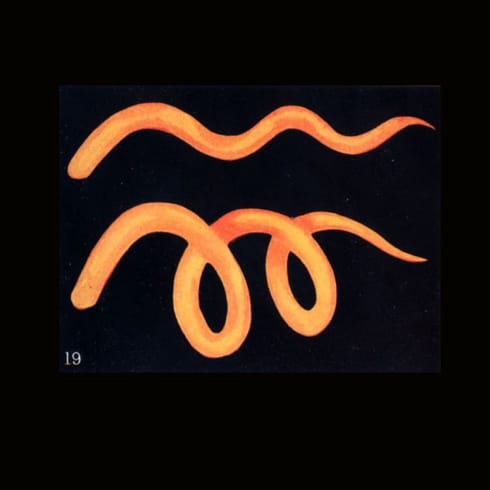

A selection of objects that we designed for the Museum of Lost Futures.

Then the pair was invited to take an object that resonated with them into the dining room, where they would take it in turns to ask each other questions:

- What kind of world is this object from? What is its story?

- Why did this object speak to you?

- Where are the chains in your life? What keeps you small?

- What haunts you about your world?

- What must crumble for you to have the life you need?

- What patterns have you noticed [in the other person]? What do you wish for them? What do they need to hear?

Finally, people were asked to move into the theatre, where they would watch a message from the pair who had been through the museum before them, write a message to their future selves about how they keep building the future they want to build, and record a message to the next pair to go through the museum.

What we learned

Some things were unclear about the experience, and we had some technical problems, but none of these seemed to ruin the experience for people. A lot of people had profoundly impactful experiences in the Museum—perhaps more than we were even expecting. People reflected on their hopes, fears, and dreams, and the closeness of the relationship between the two people attending often made the conversation in the dining room incredibly vulnerable and intimate. People cried, hugged each other, held hands, and left the Museum with more hope and understanding than they entered with.

Placing objects from potential worlds/futures/histories alongside objects from our world introduced an uncertainty to the experience that was destabilising for people—to great effect. We refer to this as semi-fiction, and we feel that it really helps people to enter into an imaginative and possibility-centric space, as it makes people aware that even our own world and present reality is constructed. If something is constructed, it can be deconstructed, and we can build something new.

Immersive experiences have a great potential for helping people to feel new things and connect these to new imaginaries of the future. It's more critical than ever to help people develop their ability to imagine something different than our current world. We especially think it's really important that people are able to develop an embodied sense of what hope feels like, of noticing what the chains in their life feel like, and to notice how they are haunted. We can only build new worlds by confronting what is "to be done" about our haunting (as Avery Gordon puts it). Immersive experiences can weave together designed objects, facilitation through card games, and stories told through audio soundscapes. Using all of these methods at once more richly helps to build someone's possibility landscape.

What we made

We made:

- An immersive experience called the Museum of Lost Futures

- Several objects from potential worlds, including a Gamete Donation Kit, surveillance posters, an instruction manual for a crime detection camera, and a letter from a future justice system

- A story that ran throughout the experience

- A soundscape that guided people through the experience

What's next?

We'll be going back to people involved in the project soon to ask if they'd like to participate in its next stage, which will remind them of the messages they sent into the future to themselves, and see how these intentions are playing out several months later. We're exploring this as a speculative way to explore longer-term impacts of individual events.