Putting frontline workers at the heart of learning and evaluation

For the past year, we’ve been putting together an approach that prioritises the expertise and insights of frontline workers in an evaluation and learning programme. Here’s how we’ve been doing it.

We see a lot of learning and evaluation approaches that are boring, extractive, and disempower frontline workers. That feels wild to us. The expertise of frontline workers needs to be at the forefront of evaluation and learning programmes because they’re the ones delivering services, which means they’re the ones that actually know what’s happening. Yet we see evaluation programmes that seem to think of workers as people to be extracted from for metrics or amalgamations of stories, instead of taking opportunities to centre workers’ reflections on their work practices.

For the past year, we’ve been putting together an approach that prioritises the expertise and insights of frontline workers in an evaluation and learning programme. Here’s how we’ve been doing it.

How it works

We’re the Learning Partner for a programme of 20 different youth work projects in 20 different geographical areas across the UK. For each project, we have recruited one “Learning Steward”: a frontline youth worker who pays special attention to three things alongside their everyday work:

- Storytelling

- Strategies*

- Signals*

*Read what we mean by signals and strategies at links.fractals.coop/signals

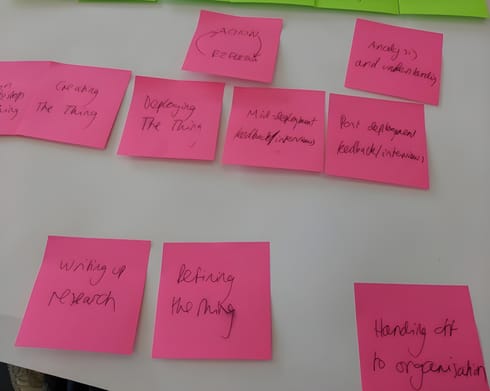

Storytelling

Collecting and telling stories is crucial to good evaluation and learning practice. We need to collect and tell stories about our project before we can start to think about whether what’s happening is going to lead to the kinds of changes we’re hoping to make.

This story collecting and telling activity is about creating shared memories and stories about the project areas. It generates a history of what’s happening on the ground from different perspectives of colleagues, so you can answer the question, “What’s happening?”

Strategies

Strategies are craft and practice. They’re dynamic and flexible, adapting to the situations we find ourselves in. If we’re going to adapt to a changing situation, we need to be able to know how to refine our strategies.

Refining strategies involves understanding the challenges and opportunities of the strategies that are being used. That might mean finding out something works very **differently in practice than you’d hoped in theory, finding out about unintended impacts, or paying attention to promising new directions. Refining our strategies means continuously improving our practice so that it is aligned with the change we’re trying to make and the signals we’re hearing.

Signals

We talk about signals rather than outcomes in our work. Signals are what we might see or notice if our strategies are effective, or the signs that we’re going off course.

Listening to signals means understanding the impacts we’re having in the world. Did someone directly tell us that a session meant a lot to them? Did someone start behaving differently after coming to the group for a while? Has the organisation started to act more in line with the way we were hoping to influence them? What am I feeling as someone working in this project?

These are all signals, and we need to collect and make sense of them if we’re going to learn from our strategies. They’re clear indicators that something might need to shift about the way we work, or that we’re on the right track.

Why we work this way

This way of working supports some of our co-ops’ values: vulnerable, honest, and caring relationships are the norm, and work is focused on creative, meaningful collaboration that supports people’s flourishing and that helps to meet our collective needs.

In developing this approach, we’ve been inspired by participatory action research, communities of practice, and Human Learning Systems. It turns our work as learning partners into acting as critical friends, strategically spotting patterns and amplifying experiences where needed. There are benefits to that for us—it gives us a rich picture of what’s actually happening on the ground and distributes responsibility for capturing and relaying information—but we think the strength of this approach is putting workers at the very front of it. It leads to better practice and working conditions for workers, and better outcomes for service users.

Doing learning and evaluation this way gives frontline workers the room to create deeper relationships between each other, especially in a group that is geographically distributed. If something feels off, they can bring it for discussion with other workers. If they want to celebrate a success, they have a community around them cheering them on. If they need a system or structure to change, they can become a united voice amassing evidence of why the default way of doing things doesn’t work for them. By valuing and trusting staff to share their experiences, they become more confident in speaking up and experimenting when changes are needed.