Theories of change for alignment and signalfinding

Are you using your theory of change for evaluation, or for alignment?

There are a thousand different ways to make and use a theory of change, but conventional wisdom says the key features are something like: assumptions, inputs, activities, outcomes, long-term outcomes, outputs. This is typically based on the idea that theories of change are really good tools to use for evaluation and outcomes measurement.

We don’t think they are. Over-quantifying a project through this chain of Inputs > Activities > Outcomes > Outputs doesn’t actually help to understand what a given project is doing. Outcomes pathways create an illusion of certainty that isn’t actually useful for practitioners. They might produce a KPI that you can report up a hierarchy that you’ve achieved, but they don’t match how change actually happens in the world or how people speak about it.

The idea behind an outcome is to try to understand the impact a given intervention is making. They take a programme’s intentions, and distil them into a number of clearly articulated desired states. Yet it’s really complicated, expensive, and time-intensive to actually find out about those desired states, and how much someone being in a desired state is because of a project, so people turn to proxies for those states. Rather than whether someone’s more likely to get a job, we’ll find out if they feel like they know more about their skills.

But these proxies still don’t work, because changes in people’s states—outcomes—are emergent properties of complex systems. Projects can’t deliver outcomes. So where does that leave theories of change?

Alignment and signalfinding

In our experience, theories of change are most useful when they’re used to help a team (or a project, or an organisation) align, to come into rhythm with each other. It’s about creating shared language, shared ownership of a vision, shared practice—and perhaps most importantly of all, shared accountability.

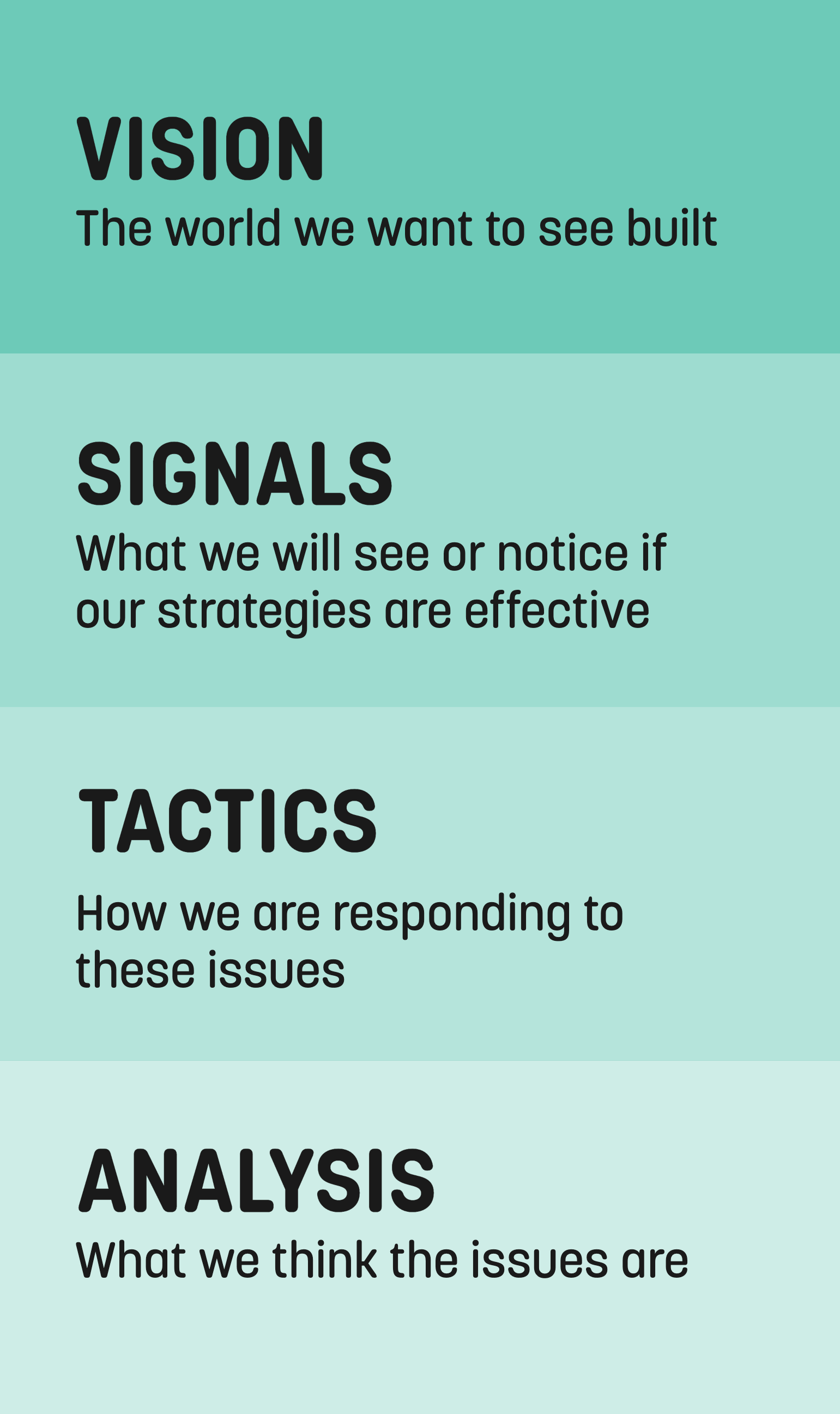

When we make a theory of change, we like to help teams come together to think about their analysis of the situation they’re working in, their tactics (or strategies) for making changes to that situation, the signals they want to pay attention after using those tactics, and the vision they’re working towards. Analysis > Tactics > Signals > Vision.

Tactics—how we respond to our analysis

Tactics are craft and practice. They’re dynamic and flexible, and should adapt to the situations we find ourselves in. We focus on tactics rather than activities because we think that change happens by skilled practitioners drawing from a toolkit of methods rather than delivering discrete sessions. Each member of a team can draw on different tactics at different times, but they’re all in service of the same vision.

Sometimes, we'll refer to tactics as strategies. There's no difference between these, except for the language being used. We find that campaigning organisations already think in terms of tactics, so the language makes sense to them. Charities that deliver services might find it easier to think about strategies instead.

Analysis—what we think is happening

Ideally, tactics are informed by an analysis of the situations we’re working in. They help a team to build out a shared analysis of the systems they’re working in, who has power, and the problems they’re facing. The process of building a shared analysis often surfaces very disparate analyses. We don’t necessarily need to reach consensus on these aspects, but we do need to find consistency in our orientation towards these, because they help people to understand the differences in how other members of the team interpret their work.

Vision—the world we want to see built

People have a tendency to think that vision is easy, but we’re constantly trying to push people towards thinking about more expansive and radical visions of worlds they really want to live in. Your vision shouldn’t be “A world where that bad thing doesn’t happen”, but more like “A world where the positive alternative we can imagine is the norm and our lives are changed in innumerable ways”. You want to get tingles when you think about your vision. It might even provoke part of you to think surely that’s a bit much. It should be. This is a whole new kind of world you’re fighting for.

Signals—what we will see or notice if our tactics are effective

Signals are probably the aspect of our approach that is most different than conventional theory of change practice. We talk about signals as ‘what we might see or notice if our tactics are effective’. We tried to find words that were as close to practitioners natural language as possible. You might deliver a session, and then the next month you might notice someone is using language in a way you used it, starting a hobby you recommended to them, going on a protest you helped them to find. These are signals that your tactics are effective. It doesn’t matter if that signal is attributable to you or not. We’re trying to create the world in our vision—does it really matter who is responsible for building it?

Of course, we might want to understand more closely how effective our tactics are in order to understand if we need to develop new tactics—so we might create some specific learning activities where we test assumptions about our analysis, tactics, or the signals we’re noticing. That becomes part of a learning loop where we continuously refine our theory of change as things change in the world.

We’ve currently trialled this approach with two organisations who are dipping their toes into doing evaluation and learning work differently. We’ve seen teams start to build shared language where previously there was none, and we’ve started to see workers be able to talk about positive changes in language that feels right to them. We’re creatures of storytelling, and we deserve tools that help us understand our practice in a way that matches that. It’s not important to us that “Sarah has significantly improved her mental wellbeing”, but it is important to us that “Sarah can finally pick up the phone to call a friend when she’s not doing well”.

Evaluation and learning tools need to match up with the ways people speak, the way we envision change, and the ways we actually work. Otherwise, they’re just a tool of bureaucracy and capital that gets in the way of skilled practitioners doing their best work.