Getting started with hacking games

If you’ve been following our work, you will know that we love making games and games-inspired tools. In this post, we’re going to talk you through how you might get started by hacking an already existing game—whilst talking about how we did that on a recent project.

If you’ve been following our work on using games for research, engagement, and impact, you will know that we love making games and games-inspired tools. Whether you’re communicating the findings of a research project, helping people to understand the experiences that underpin your work, or trying to explore the wild west of user research ethics, games have something to offer.

But of course we think that. We make games all the time. We play a lot of games and talk to each other about games and have serious conversations that say silly things to each other like “this is really similar to that one bit of scenario 23 in Betrayal at House on the Hill”. When games-y people like us start talking about games, you might just start thinking “well that’s nice for them, but how can I do anything with games”?

In this post, we’re going to talk you through how you might get started by hacking an already existing game—whilst talking about how we did that on a recent project.

What is game hacking?

“Game hacking [is] a critical–creative research practice that interrogates and transforms existing games to reveal the ideologies embedded in their systems and mechanics.“ (Germaine & Wake, 2025)

In our practice game hacking is the act of taking a game, and manipulating or redesigning it to explore the unarticulated worldview contained within the games’ systems and mechanics. Game hacking helps us understand the politics and practices embedded in games we play, allowing us to think about how they might be used as a design material for other games.

This might be to express a similar kind of politics or worldview, or to critique the original view. When we make games, we often start by hacking an existing game which we feel has a resonant politics. By borrowing pieces and ideas from other games, we can quickly get further along in the design process whilst remaining conscious of the underlying purpose and ideas communicated through the game. This can look like taking game mechanics from games that are ideologically aligned with the brief and adapting them to help kick-start thinking about how these mechanics might work (and how they might not) in new contexts.

Finding the right game to hack

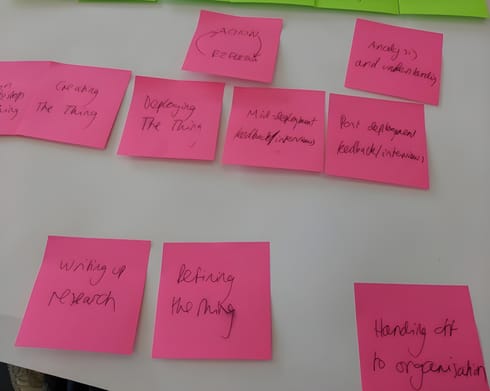

We worked with Dr Temidayo Eseonu to design a game called Belonging, a role-playing game for teachers and other educators that helps them identify ways to shift their pedagogy and school practices and processes to create cultures of deeper belonging for more students and staff. If you’d like to hear more about the project itself, you can read it here.

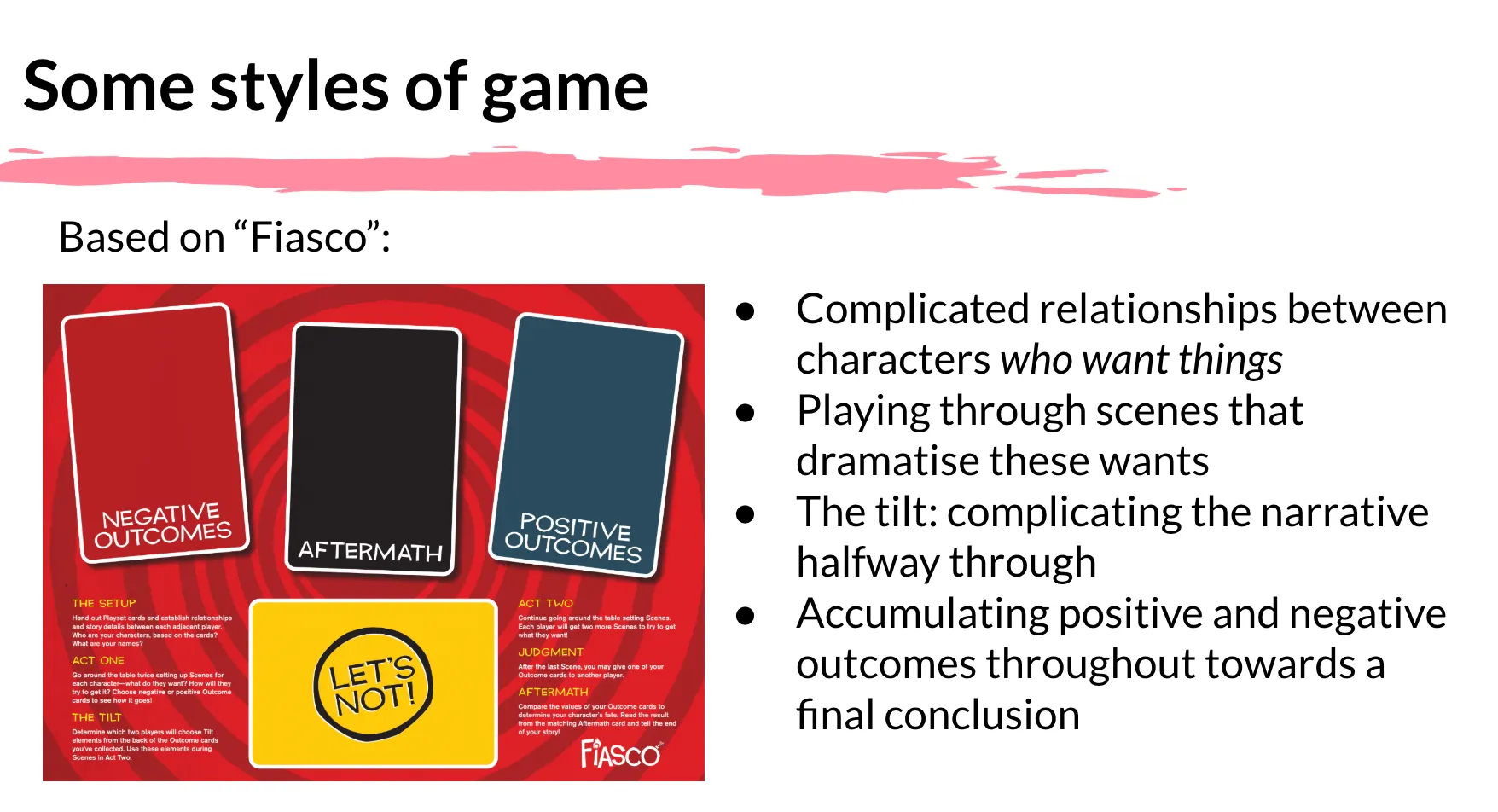

From the proposal we had developed with Dayo, we were drawn to role-playing games that have rich, clear prompts, and structures for creating short role playing scenes. Our starting points were Fiasco and For the Queen.

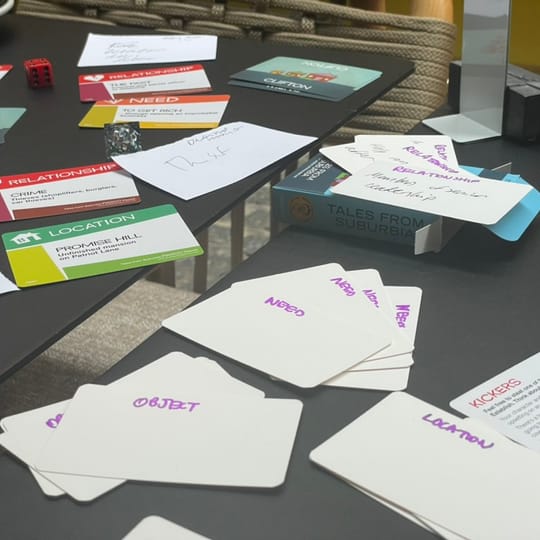

Fiasco is a card and dice-based role-playing game, where players create characters with complicated relationships who want something, and then play through scenes with these characters to dramatise these wants. Each scene is set up by one player and resolved by another, building towards a positive or negative outcome. Halfway through, there’s a tilt, which complicates the narrative. The unarticulated worldview in Fiasco might depend on the particular scenario you’re playing, but the game itself prompts collaboration, shared agency, and an understanding that we can’t control the outcomes of what we do in the world.

For the Queen is an entirely card-based game. Each card is a question, and there is a final card buried in the back half of the deck. Players work out their character as they play by answering questions, and a narrative begins to shape up. It’s a zero barrier to entry game and promotes an emergent sense of discovery throughout. Whilst it might appear that the For the Queen’s politics is about monarchy, in practice it tends to be more about exploring our relationships to absolute power, and how we might align or distance ourselves from it.

How we hacked them

We liked the way character creation in Fiasco worked—built around a relationship and a need, object, or location. We thought this kind of character creation would work really well for teachers who might not be used to roleplaying, and give them some clear elements to cling on to. We decided to focus only on relationships and needs, because we felt they were the most important elements for the experience we were trying to craft. We created some relationships and needs that evoked dynamics Dayo had seen in her research, such as:

- [Need] To reach the next level of your career

- [Need] To change something

- [Need] To keep doing what you’re doing

- [Relationship] One of you got the job the other wanted

- [Relationship] You both have a shared belief or faith

By having broad yet still specific cards, we created prompts that anyone would be able to work with. Lots of games like this work with the principle of apophenia or forced association—we will be able to find something from our own experiences that we think can we can explore inside of this specificity.

We didn’t think the freeform scenes of Fiasco would work for our context, because the excitement of a game that might be played on a training day is a bit lower than the heists and cinematic capers of a normal game of Fiasco. Instead, we decided to draw on the scene prompts of For the Queen. Doing this meant that we could introduce some of the belonging-specific context and experiences that Dayo had learned about from the research she did with racially minoritised young people.

After playtesting, we also introduced “potential endings” to the scenes. These gave players a clear sense of a potential direction the scene might go in, and acted as an effective cue to end the scene. Yet they didn’t prescribe how scene had to go, giving players a space to maximise their agency and autonomy, try out new experiences, and explore different potentials. In playtesting, we saw players being bolder than they might normally be, trying out new strategies, and challenging the behaviour of other characters.

Finally, we designed an activity to add to the end of the game to more firmly embed the insights from play into practice. We used our facilitation experience to design an end-of-game discussion that gave space for members of staff with more privilege to speak up about things that have felt uncomfortable about them, and continued to use game mechanics in this discussion to prevent the discomfort of staff members who might be unwilling to change controlling the flow of discussion.

Designing for frame shifting

By supporting players of the game to create interesting characters that have needs that reflect the kinds of people that might actually exist in an educational environment—and then having them play through realistic scenes—we created a space of play that overlapped with people’s everyday work environments.

This helped us to develop our idea of frame shifting, which is playing with the space of the game and the social frame the game is played in. You can read more about how we design for frame shifting here.

If we deliberately design games to overlap social frames we can play experiences matter in people’s everyday lives, not just within the game. The making and playing of games creates an alternative temporary space for players to try new things, pick up what resonates with them, and bring those back to their everyday lives and work.

If you’re interested in hacking a game for research or just for fun, get in touch or read about how we use games for research, engagement, and impact.