Designing games to build new futures

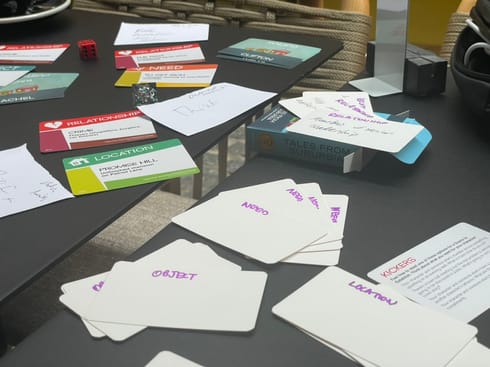

Last week, we visited the Manchester Game Centre for their annual conference, Multiplatform. This year’s theme was Rituals of Play, and we were there to present our work on designing and using games as a way of building better futures, and to host a play session of our new game The Ritual of Rebinding.

We had a great time meeting likeminded games designers, academics, students and others in the games space, talking about the occulture of games. In our presentation, “Rituals for building futures: games as speculative praxis”, we spoke about how games and games-making can act as a form of “speculative praxis”, a sustained political effort to build new possibilities for the future through creative acts of speculation.

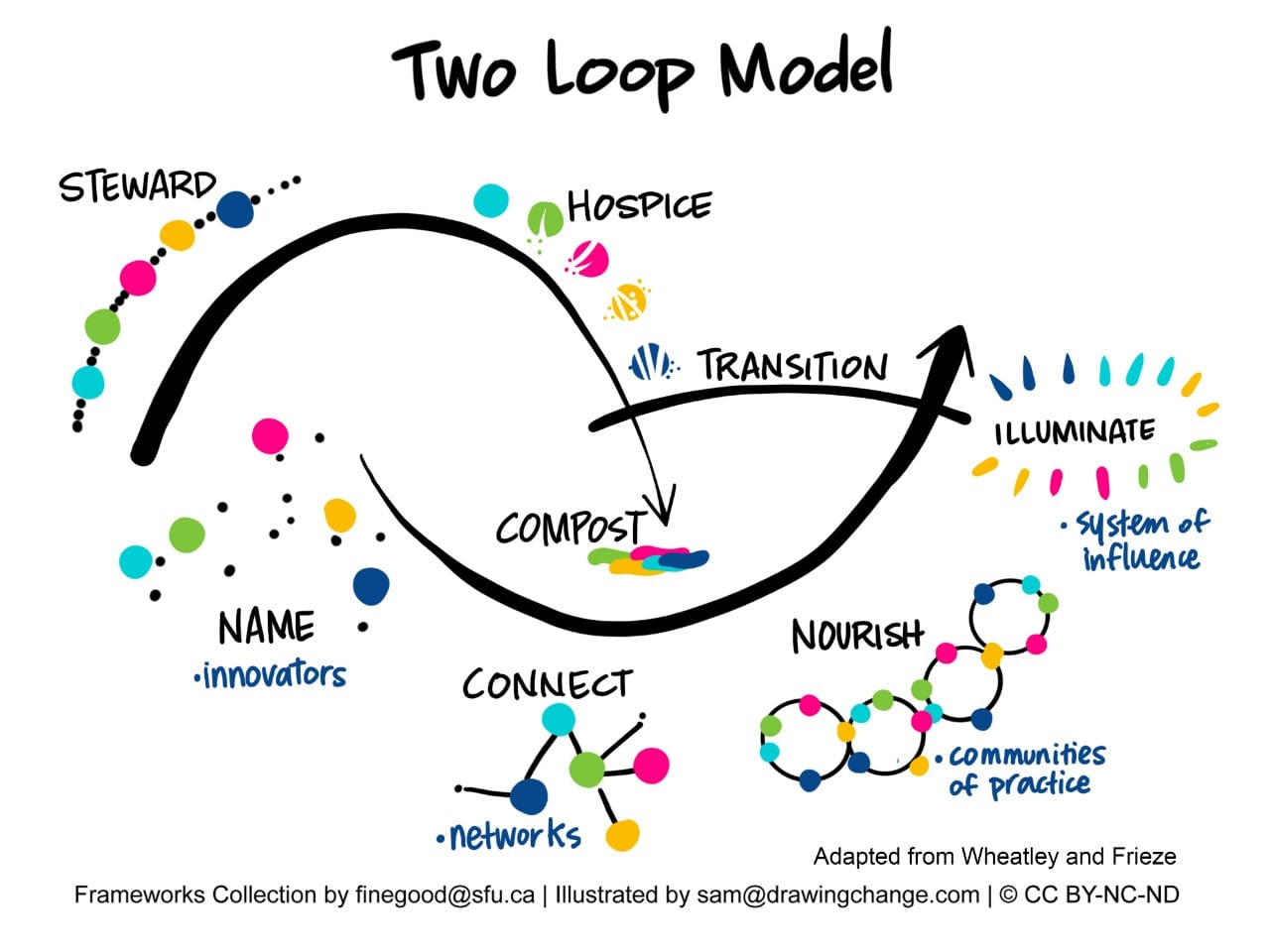

We use systems thinking in our work to understand the contexts we work in. Things have a tendency to get stuck, though. It’s what Lauren Berlant called a “suspended imaginary” and what Mark Fisher called “the slow cancellation of the future”. The dominant system is being hospiced and composted to create the fertile soil of an emergent system, and people are planting seeds, trying to grow something new. But it struggles to.

That’s why we need to cultivate what Ruha Benjamin calls our “radical imagination” - or as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation call it, the “imagination infrastructures” that support the development of our “collective imagination”. We think analogue games are really good at doing that.

Games as imagination infrastructures

Analogue games are one of the most active parts of our collective imagination as a society. Think of the ways that you start constructing tiny narratives during a game of Catan, Monopoly, or Pandemic. You’re not just playing the game, you’re briefly stepping into a different world where you really care about the fact that someone just stole your wheat, again.

As part of our work on speculative praxis (experimental creative action that opens up possibilities for people), we use games in two main ways.

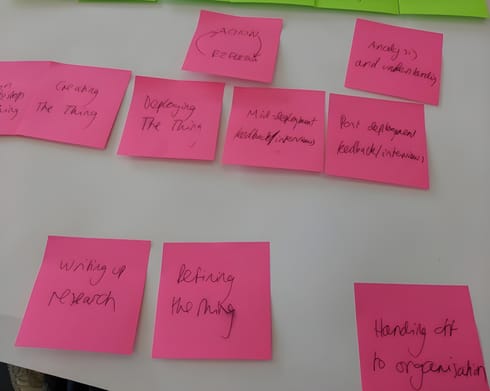

- Speculative interventions, where we create spaces or experiences where new kinds of interaction become possible. The idea here is to create new possibilities through new spaces with different rules and constraints.

- Object-based interactions, where we focus on designing an object or set of tools that change something about the interaction qualities of a space, process, or system.

We use this throughout our work. The Tomorrow Deck, for example, isn’t quite a game but is an object-based interaction, opening up new possibilities for conversation. Our Campfire workshop as part of the Facilitating Bravery Initiative (that we co-ran with our friends at the Collective Impact Agency) created a speculative intervention where the way that teams interacted with each other was different than during the rest of the work day.

These work because games engage players in a “double consciousness” of the game world, the real world, and the interface between these. You’re simultaneously:

- A person in a larger social setting (person)

- A player in a game (player)

- A character in a simulated world (character)

You move flexibly between these social frames as you play. You roll the dice, proceed seven spaces, land on another player's hotel (player), desperately beg them not to make you pay rent (character), then tell everyone you're just going to grab a snack (person). The movement between frames doesn't hurt your immersion: it enhances it.

This is often spoken about as “bleed” in LARPs or tabletop role-playing games. It's the spillover from player to character or vice versa. Sometimes this is spoken about as something undesirable, but we think that bleed can be a transformative and potentially emancipatory experience.

We call the process of designing games that elicit these experiences designing for frame shifting. This kind of design foregrounds the movement between social frames as part of the game, perhaps blurring the line between each frame. Am I taking this action as my character inside of a game world, or am I taking this action as a person in my wider social setting? More casually, these kinds of games might be called “meta”.

If we deliberately design games to overlap social frames or move between them, experiences we have within one frame can influence our experiences at other frames. We can make player experiences matter in people’s everyday lives, not just within the game. The making and playing of games creates an alternative temporary space for players to try new things, pick up what resonates with them, and bring those back to their everyday lives.

If you’re interested in understanding more, you can read our full presentation below. Our script is in the presenter notes, so you can follow along as if you were there.

You can read more about The Ritual of Rebinding here (and soon, on its own page).

If you‘re interested in how you could use games in your work as part of meaningful experiences that really stick with people, contact us and we’d love to chat.